AGI, or Artificial General Intelligence, is the holy grail of much AI research. It is an AI that can learn anything, at least anything a human can learn. If we could achieve it, humans would never need to work again, or at least the nature of our work would shift far more dramatically than it ever has in human history.

Some people, particularly AI “doomers” (people who think achieving AGI strongly threatens an apocolypse), seem to believe that if we achieved AGI, it would possess magical abilities to break all encryption or determine objective truths.

My use of the word “magical” reveals what I think about this notion: it is utterly foolish, preposterous, ridiculous, and just plain stupid!

Consider, for instance, the halting problem. Can we write a computer program that takes in another program and tells us whether it will come to a halt, or run forever? Alan Turing proved this to be mathematically impossible. No such program can be written. AGI won’t be able to do it either.

Similar with encryption; AGI will not magically discover number theory impossibilities that suddenly allow all encryption to be broken in a practical amount of time.

AGI will not be able to break mathematical limits that we are already certain of. Why do some people seem to imagine that it will be able to do impossible things like this?

Perhaps the silliest notion of all is that AGI will somehow be able to spit out objective truths, somehow avoiding the ambiguities that result in human intelligences’ conflicting conclusions. Where the heck would such objective conclusions come from? Will it be privy to some magical data that humans cannot perceive? How would it get such data? Will it recognize secret codes in the data we train it with?

Even with human intelligence, we can draw multiple conflicting conclusions from the same data. See my previous post about the meaning of facts (i.e. data). When we come to conflicting conclusions, what do we do? We expirement! If we can, at least. (Otherwise we just argue about it, I guess.) And the point of such experimenting is not to find objective truth, since we can’t, but rather to be able to make useful predictions. Doing this leads to that, so if you want that, do this. And then we build on it. Hmmm, so if this leads to that, does this other related thing lead to that other related thing? Experiment, find out. (On a side note, AGI is, in my opinion, all about figuring out how human intelligence is capable of making that leap from one set of relations to another, or, to put another way, how we are able to generalize predictive relationships. It comes naturally to us (to some more than others), but we have no idea how to program a computer to do it.1)

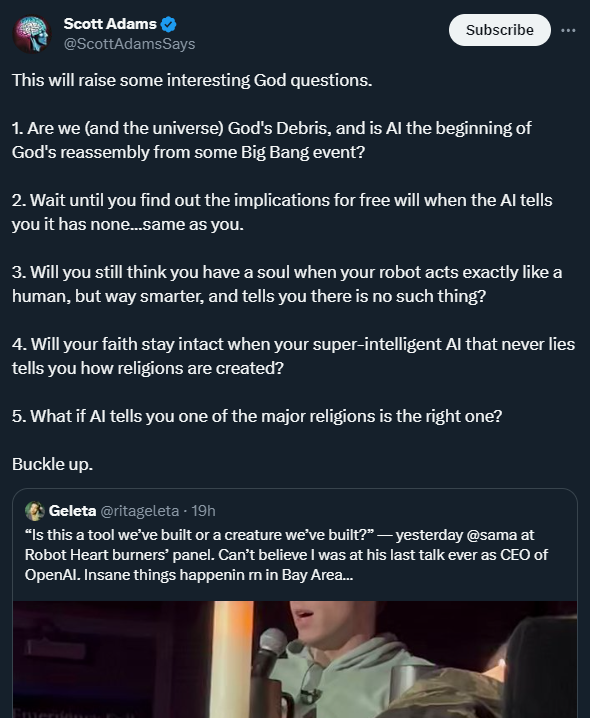

So Dilbert creator Scott Adams asks some silly questions on Twitter regarding AI and God:

I shall now try to answer these questions:

1. No, because that’s not what God is.

2. Is that a question? Anyway, here Adams seems to be supposing that AI, or AGI, is synonymous with conscious experience itself, which is quite a leap! Even if we believed it, why should that mean anything to a human, whose intelligence is not, by definition, artificial? Finally, I’m not sure what Adams’s understanding of free will is. Free will is the experience of making a conscious choice. It is not (necessarily) the universe’s ability to do something magically undeterministic in a human brain. (For instance, see compatibilism.)

3. Yes; where does Adams think beliefs in souls comes from? For that matter, how would a human know if a robot is “way smarter”? We’d need some way to relate to it, to find meaning in its output.2 But it’s still a non-sequitur to conclude that it would somehow conclude something about the existence of souls based on some necessarily knowable given data, and that such a conclusion would then be objective. One might as well doubt the existence of souls because some “way smarter” atheist says so.

4. How religions are “created”, in the general sense, has nothing to do with faith in them. That’s like doubting the usefulness of a scientific invention by learning how it was invented. Also, is an AI “that never lies” supposed to be the same as an AI that is never wrong? Because that cannot exist, as explained above.

5. How would AI come to such a conclusion? From training data? Or it opens up a spiritual portal to the God dimension?

All these questions seem to be based on a belief that some powerful AI would gain some kind of spiritual perception from data alone.

To be fair, these questions do point to the philosophical conundrums inherent in a materialistic / deterministic understanding of the human brain and its ability to perceive and believe in God. We don’t know how the brain does it. One could say, “Oh, one just gets it from his parents!3” but that is hardly a satisfactory explanation. Firstly, it implies either an infinite regress, which explains nothing, or that some human was the first to create the idea, which just leads back to the initial question of how it was possible for a human brain to do so. Secondly, even if learned, the human brain must have some prior ability to perceive its meaning; where does this come from? How did it form? I ask such questions not to imply that a supernatural cause is required (that’s a separate issue / argument), I’m only pointing out that it’s something we don’t yet understand from a scientific point of view. (And understanding it would not shake one’s faith, anymore than thinking that understanding that two and two is four is manifested as neural signals in your brain makes two and two not actually four. That is, if you are to understand something to be true, it will obviously be reflected in a physical manifestation in your brain somehow.)

Questions of objective truth aside, we could then ask: could a sufficiently advanced AI believe in and perceive God as humans do? It’s certainly an interesting question, but it implies nothing about human belief in and of itself, because, again, it would give us no greater pathway to objective truth.

Finally, to answer Sam Altman (in the tweet Scott Adams was quoting): It’s a tool. You did not create a creature. Don’t flatter yourself!

So those were just some random ramblings on AI and God. I hope you enjoyed. It was all actually written by AI!

Just kidding. But what if it was?!

(Artwork is by AI though, obviously. DALL-E 3.)